My name is Katie and I live in Sheffield. I am a mother with a nine year old son who is my carer.

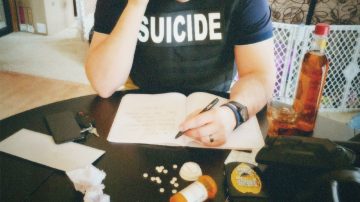

I have been affected by suicide most of my life in different ways. By the age of 36, I had attempted suicide several times and lost two of my best friends to it. Suicide is still part of my life.

There is a lot of stigma about mental health. I have been diagnosed with what is called Personality Disorder. Some people hear Personality Disorder and assume we are evil and dangerous, and the term ‘disorder’ doesn’t help with that misconception.

I think living with mental illness is harder for women because we are supposed to be stable homemakers, responsible for looking after children and family no matter what. I have been told I shouldn’t have had children because my son has been under child protection plan and social services. It makes me feel very guilty knowing my mental illness has obviously affected my son. But I am doing my best to ensure he gets the support he needs, so he doesn’t grow up facing the same mental health challenges.

My childhood was difficult, though I prefer not to talk about it. I got bullied a lot at school which led to my self-loathing and self-harming. When I was 15, I started self-harming and it gradually worsened. Most of the time, I felt disconnected from my body, heard voices, and developed an intense attachment to people.

The most significant suicide attempt happened in 2007 when I tried to set myself and my home on fire. At that time, I hadn’t been diagnosed with any mental health condition, so I was charged with arson and ended up in prison. It was a horrible experience which worsened my mental health. In prison, I met a prolific serial killer who described in detail the horrific things she had done to her victims. No one wants those images in their heads. I continue to experience flashbacks to those days which still triggers me. I kept shelf-harming while in prison.

After six months, my solicitor arranged for a private psychiatrist who did a lot of tests and finally diagnosed me with Personality Disorder. In some ways, it was a kind of relief—it explained what I had been going through, and also saved me from spending at least 20 years in prison. However, even with the diagnosis, I didn’t receive help or support when I was there.

After I was released from prison, I started seeing a psychiatrist every week and then was referred to the Therapeutic Community Centre in Birmingham. I stayed there for 12 months. The centre was a residential unit for people with personality disorder. It wasn’t like a formal hospital setting but had a supportive community atmosphere which was very helpful. Instead of being sectioned in a hospital or isolated at home, we lived together, ate together, went shopping, and had psychotherapy. We also had different kinds of art-based therapies including drama which I enjoyed a lot. Sadly, they shut this unit down as a part of the government’s ‘cost-saving’ policy, despite how helpful it was for people like me.

In an Ideal World

I still struggle with my mental health problems and receive help from mental health services. In my opinion, the whole system is underfunded. We need more funding, better training, and more mental health support workers. In an ideal world, there would be more Therapeutic Community Centres like the one I attended in Birmingham which could help people improve their mental health, especially those with Personality Disorder.

More support is especially crucial for younger people so their mental health issues can be addressed early before they worsen in adulthood. Struggling with mental health challenges becomes much harder when you are an adult. It would be really helpful to have more support groups for mothers, children, and young carers who are affected by mental illness.

The police need better training and greater awareness of mental health so people like me are not sent to prison for self-harming.

When someone is in crisis, immediate help is needed. I have called Out of Hours helplines many times, but the response varies depending on who you get on the other end of the phone. Sometimes, it can take hours to get a call back, and by then, it might be too late. My experience has been positive but I know others who have had negative experiences with the crisis team.

The Sheffield Support Hub in the city centre is helpful if people need help. The Decision Unit at the Longley Centre at the Northern General Hospital is also a good, quiet place, although it is very difficult to get in because there aren’t enough beds.

Finding Little Pleasure in Everyday Life

It might seem unimportant, but finding little pleasures in everyday life—like bird’s singing, sunshine, and being out in nature—makes a difference. It’s hard to notice small things sometimes, but they are there.

Being with my son and my wife helps me a lot. I have a blanket with our pictures printed on it, and it reminds me of hope and happier times. It also reminds me that we can be happy again.

Whenever I go to the Decision Unit, I take it with me, it goes everywhere with me.

Creativity is another helpful thing for me. Drama is my favourite activity. I wrote a story about my mental health from the point of view of my boy. When I do drama, I feel alive. I am also involved with SAYit (LGBT) and participate in fundraising events and activities there. I enjoy watching rugby and I do abstract painting.

My message to those out there who are suffering is: hang in there! You will find hope again.

This story by Katie is part of Suicide Prevention project funded by Sheffield City Council and run by Sheffield Flourish. Through one-to-one conversations short personal stories have been created, aiming to spread awareness around suicide, and break down stigma.